Disclaimer: This story has been republished with permission from Entrepreneur.com.

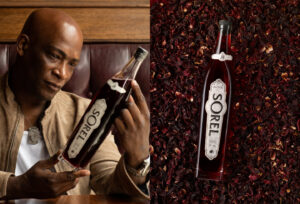

Jackie Summers, founder of Jack From Brooklyn, Inc. and its widely acclaimed Sorel Liqueur, knows what it takes to make a comeback.

Summers says he was the only licensed Black distiller in the U.S. post-Prohibition in 2012, and when he launched his hibiscus-based liqueur that year, he had to navigate an industry that wasn’t set up for him to succeed.

“I started working the market, and when I went to accounts, no one believed I was the brand owner,” Summers tells Entrepreneur. “To this day, most places I go (and I’ve been to thousands) have never met a Black liquor brand owner before.”

In spite of the odds, the brand gained immediate recognition among cocktail enthusiasts.

Then things began to fall apart.

Summers’ distillery in Red Hook was ravaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, and insurance wouldn’t cover the damages. Still, he managed to rebuild by 2013, recapturing Sorel’s momentum until soaring demand and Summers’ do-it-all approach brought the brand to a halt once again — this time, for several years.

But that still wasn’t the end of the story, which, Summers says, actually begins thousands of years ago in Africa, where “the red drink” made from hibiscus flower — and the basis for Sorel — originated.

“Fast forward to 500 years ago, and the Transatlantic trade starts,” Summers says. “Now, bodies and spices are being stolen from the continent of Africa and transported.”

The hibiscus flower came with them, taking root in the Caribbean.

And though the recipe for the red drink also known as sorrel wasn’t written down, its devotees kept it alive through oral tradition.

“These are people who had everything stolen from them,” Summers says. “They were taken from their home; families were destroyed. They were given new names, forced to practice a different religion. They had every part of their identities destroyed. But somehow they preserved this cultural identifier.”

Naturally, variations in the beverage arose between nations, based on the spices traded at their ports.

“The difference in spices that were traded on various islands correlated directly to the ethnicities of the indentured servants working there,” Summers explains. “Jamaica, for example, had a high number of Chinese indentured servants, hence ginger and cardamom. Islands like Trinidad and Tobago had a high influx of East Indian indentured servants who brought their spices with them, so cinnamon, nutmeg and clove.”

Summers’ own family would carry the tradition of sorrel with them from Barbados to Harlem, New York in 1920. His grandfather, a chef, taught his mother how to make sorrel, and his mother taught him.

Summers also recalls enjoying the drink at the annual Caribbean Day Parade, where two million people from every island celebrated on the Eastern Parkway with costumes, dancing, flags and food.

“I remember being this child,” Summers says, “and I didn’t care about all of the other stuff — just beef patties and roti and curried goat, all this delicious food, and washing it down with this red drink, non-alcoholic because I was a kid.”

“What I really want to do is day drink. I want to be around interesting people in the middle of my day, in the middle of the week”

For 20 years, Summers batched his own version of sorrel in his kitchen “like a good Caribbean boy,” making it for parties and barbecues with family and friends.

But a cancer scare in 2010 would change the trajectory of Summers’ life — and his relationship with the red drink that had always been part of it.

“My doctor found a tumor inside my spine the size of a golf ball,” Summers says. “He said, ‘You have a 95% chance of death and 50% chance of paralysis if you live. You should organize your paperwork.’ I lived, and the experience will adjust your perspective.”

Summers was the director of media and production at a fashion magazine at the time, and he asked himself what his true priorities were.

“What I really want to do is day drink,” Summers says. “I want to be around interesting people in the middle of my day, in the middle of the week. I want to have great conversations with great food and beverage, and I want to monetize it.”

When he couldn’t figure out who was going to pay him to enjoy that lifestyle, he decided to launch a liquor brand.

Summers started with the sorrel product itself: He needed to compensate for the acidity of hibiscus and make the drink shelf-stable. It took 624 tries to get it just right.

“I [compensated for the acidity] by giving it the right balance of other botanicals,” Summers explains. “So my version of this beverage — and there’s no definitive version of it — has cloves to add brightness, cinnamon for warmth, nutmeg to add a dry finish at the end, and it’s got ginger to almost perfectly mask the heat of the alcohol. So you never actually taste booze; you just feel booze.”

And to make the red drink last?

“The organic matter in the base mix is removed in the form of complex polysaccharides, and everything that’s left is crystal clear and shelf-stable,” Summers says. “Again, I am not a food scientist. It took me a long time to figure that out. But that’s my contribution to this centuries-old story.”

The decision to drop the additional “r” in “sorrel” for Sorel’s brand name was two-fold.

“First, I have a speech impediment and have great difficulty pronouncing the letter ‘r,’” Summers says. “However, I had eight years of enunciation lessons in public school. One of the things I learned was: words that end in a down sound are sad. ‘Sorrel’ is a sad word. ‘Sorel’ is happy, and I can pronounce it.”

Summers also notes he can’t trademark “sorrel,” as it’s generic; he’s currently in the process of trademarking “Sorel.”

The ways to enjoy Sorel are near-limitless, Summers says. Although people of Caribbean descent typically drink it straight (hot or cold), it complements an array of seasonal cocktails too. Part of Sorel’s unique appeal is in its flavor-first approach.

“Big liquor companies solve the problem [of alcohol tasting bad] by adding flavors to alcohol,” Summers explains. “So we have blueberry-flavored vodka and habanero-flavored tequila. I reverse the process. They add flavors to alcohol; I add alcohol to flavor. Flavor’s always the most important component of what we produce.”

“I figured that the people who kept this beverage alive had to go through more than I did, so I should at least try as hard as they did”

Summers had Sorel’s recipe down — the same one the brand bottles to this day. But he needed investors and a place to distill. The way he landed both is “actually a really fun story,” he says.

About six months after Summers left corporate America behind, a friend and VP at Hearst magazines asked him to lunch to consider an attractive job offer: mid-six figures, a corner office on the 32nd floor overlooking Central Park.

“In my heart, I knew I was going to tell him no,” Summers says.

But the pair met at a small burger joint on the Upper West Side, and Summers gave his friend one of the bottles he’d made in his kitchen and told him about his big idea — at that point, he didn’t yet have his license to distill or a place to do it.

A man at the next table overheard their conversation and asked if Summers was looking for investors. Summers gave him his card and an extra bottle he’d brought (“Because I live in New York City, I know to be prepared,” he says.)

The man turned out to be Alexander Bernstein, son of internationally acclaimed conductor Leonard Bernstein. He became Sorel’s first investor and made it possible for Summers to acquire the brand’s distillery in Red Hook.

Cocktail connoisseurs quickly took note of the delicious and versatile red drink.

Then, six months into the brand’s strong launch, Hurricane Sandy hit.

“Six feet of seawater in the basement,” Summers recalls. “Five feet of seawater on the first floor. All of the commodities, all of the equipment, destroyed. The building took major structural damage. Insurance did not pay a dime. FEMA did not pay a dime. The SBA rejected 90% of the applications that came out of Red Hook.”

But Summers wasn’t deterred.

“I rebuilt it with a lot of sweat, and it took every last dime to relaunch the business,” Summers says. “That really should have been the end right there. That should have stopped us. But I figured that the people who kept this beverage alive had to go through more than I did, so I should at least try as hard as they did.”

Sorel relaunched in 2013 and brought its distribution up to 22 states.

But Summers and his vice president Summer Lee, who remains with the company to this day, were “literally doing everything” themselves, and it wasn’t sustainable.

When The New York Times listed Sorel in its holiday gift guide that year, calling the drink “Christmas in a bottle,” the demand became too much to meet.

“You can do everything yourself, but you can’t do everything well,” Summers says. “I was making the product, doing sales calls, opening new markets, doing all the marketing, packaging, merchandising, keeping up all the books. I wasn’t doing a good job of all of it, and I was neglecting myself in the process. [We] could not keep up with how much product we needed to make to be a successful business.”

In the middle of it all, Summers also struggled to find investors whose values aligned with the brand’s. A series of frustrating close calls ensued: A national deal to take Sorel across the country for millions of dollars. A bidding war among three of the biggest liquor companies in the U.S. Another deal worth millions that made it to final negotiations in 2016.

None of them came to pass.

“My goal is to use the product as a vehicle for storytelling. Because story matters”

By the second half of 2016, the company had failed, and Summers was living on the street.

“I was homeless for a year and a half,” Summers says. “And I had to learn that my value was innate and not directly linked to the success or failure of my company. The company can do well, and the company can do poorly — I’m still me.”

During that time, Summers never stopped having conversations with potential investors who could help him bring the brand back. He believed Sorel’s struggle was just “a footnote in the bigger story.”

“The people who created this deserve to have this story told, and that doesn’t happen if my goal is to build it and then flip it,” Summers says. “My goal is to use the product as a vehicle for storytelling. Because story matters. So for me, the big part was not just finding money, but finding people whose intention and values align with my own.”

In addition to prioritizing investors who share his values, Summers has spent years writing, teaching and coordinating educational curricula to promote diversity and inclusion within the beverage industry.

“There was a time, and it wasn’t long ago, when we did not talk about sexism, homophobia, racism, antisemitism or any of these things in our industry,” Summers says, “and because I experienced a particular level of discrimination myself, I wanted to make sure that we could make the most level playing field possible for everyone involved.”

For many years, Summers taught a seminar called “How to Build a Longer Table.” But in 2019, when nothing had fundamentally changed, he decided to teach a different course: “How to Build Your Own Table.”

“Because it’s easier to construct something that is equitable from the ground up than to convince people who exist in structures that are not equitable that they should change for anyone’s benefit,” Summers explains.

So that’s exactly what Summers is doing with his team at Sorel today.

“There are people in my company that look like [the people at] the table that I want to sit at,” Summers says. “My vice president is a woman who is mixed race. My chief scientist is disabled in that he is blind from birth. My operations person is Latino. We are the people that we want to have at this table — all differently disadvantaged by society, but all with so much to offer and so many different skills. And it has been a blessing in that all those different perspectives come together, and they are more than the sum of their parts.”

“The only thing better than building a company that they offer you $100 million for is building a company they can’t afford”

So how did Summers get back on track and build the team he wanted to see?

When yet another negotiation with an investment group went sideways at the final stage, Summers did something he doesn’t normally do and is still working on: He asked for help.

Summers wrote to Fawn Weaver, founder and CEO of Grant Sidney, Inc. and Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey, to see if she could offer him any guidance.

Unbeknownst to Summers, just one day before, Weaver had been discussing the many Black-owned brands the Uncle Nearest Venture Fund supports in an interview when the interviewer asked if she was helping Summers. Weaver knew who Summers was — they’d met on the speaking circuit — and she didn’t think he needed any help. “Talk to Jackie,” the interviewer said.

Summers’ email arrived the next day. During their initial conversion, Weaver asked Summers what he wanted to do with the brand: Build or flip?

“And I sat back and I said to her, the only thing better than building a company that they offer you $100 million for is building a company they can’t afford,” Summers says. “And I see that’s what you are doing. If you’re asking me if I’ve got a chance to create legacy, the answer is yes.”

The Uncle Nearest Venture Fund invested $2 million in Sorel.

Sorel returned to shelves in October 2021 and “had an especially auspicious first year back,” Summers says. In 2022, Sorel entered international spirits competitions and placed gold or better 37 times.

“We cleaned up,” Summers says. “And I tell my team this all the time: Most brands go their life cycle with a gold medal, and they’re very proud of it. We got literally dozens. And while entering the competitions is no guarantee in itself, it [builds] both consumer and distributor confidence. People love to get behind the winner.”

And that’s exactly what happened. Sorel expanded to 20 states within one year. Today, it can be found at Disney resorts, Hyatt hotels, Spec’s in Texas, and BevMo and Total Wine locations across the country. Some of the major Las Vegas casinos have also put in requests.

Over the next five years, Summers says Sorel will expand somewhat, but the brand’s primary focus will be diving deeper into its current markets. “We want to dig into the story and the education,” he says. “It’s required to let people know what this is and why they should care about it. And yes, it’s delicious. But there’s more to it.”

Summers also wants to “get granular” and determine what other companies need from Sorel to succeed. “I sincerely believe you have to tie your success to other people’s success,” Summers says. “So every time I walk into a bar, restaurant or retailer, I want to know what helps them win so I can contribute to their winning. So we plan to help other companies do well, and through creating that experience, grow our own brand.”

When it comes to Sorel’s long-term future, Summers cites several exciting developments in the works.

The government of Barbados reached out to Summers; they love the brand, and Summers has had several meetings with the Ministry of Finance about building a distillery on the island.

“We’ll pay for it together so that this beverage, which came from Barbados, can be brought home,” Summers says. “Made with local hands, made with local ingredients. And then they would get behind it as a country and make sure it is in every restaurant, hotel bar and duty-free shop across the Caribbean.”

There are also plans for another U.S. distillery. Currently, Sorel is made in New Jersey at Laird & Company, the oldest distillery in the country. But the goal is to bring Sorel back to Brooklyn in the next year.

As Summers looks out even further, he hopes to expand Jack From Brooklyn’s offerings to include other products that have been waiting to be bottled for centuries.

“How many other products are out there right now that have historical [and] great cultural significance to a small group,” Summers says, “but no one has bothered to figure out how to make it shelf-stable and market it yet?”

Summers isn’t interested in making another rum or tequila, though he respects those who do — he’s on a mission to “introduce categories of one.”

Summers’ perseverance helped lay the foundation for Sorel’s triumphant return, and for those entrepreneurs hoping to make a comeback of their own? Summers has an additional word of advice: “cocoon.”

“Our culture says you must keep going at 100 miles an hour at all times,” Summers says. “If you don’t have a chance to reflect, you don’t get the opportunity to see what your strengths and weaknesses are, and how you’re going to compensate for both. It’s important to cocoon on a regular basis — whether [that’s] 20 minutes of meditation a day or being able to get away once every few weeks and spend some time in nature and quiet your mind. Once you have clarity, all sorts of things can move forward.”

Comments